This month marked the 204th birthday of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the Johnstown, New York native widely credited with setting the American women’s suffrage movement into motion.

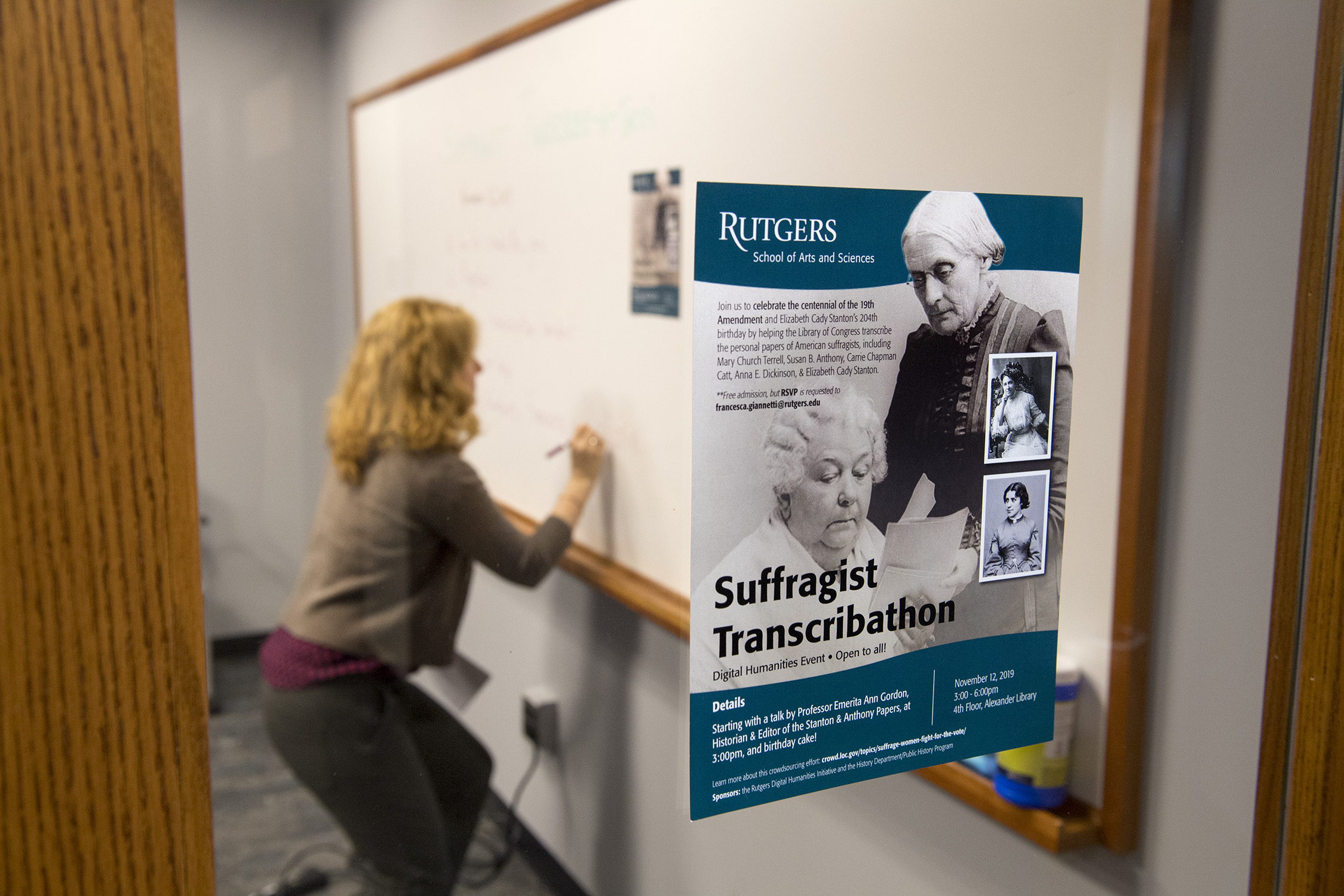

To commemorate the occasion, students and faculty gathered at Alexander Library for a Suffragist Transcribathon, where they reviewed, annotated, and transcribed scans from the personal papers of important suffragists including Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Mary Church Terrell, and Carrie Chapman Catt.

“This project is really situated to help people explore the complexity of suffrage,” said Kristin O’Brassill-Kulfan, coordinator of the Public History Program in the Department of History at Rutgers-New Brunswick and one of the event’s organizers. “We often hear about the successes, but we don’t hear about the opposition that existed so vehemently. When you go back to the sources and have people work with them directly like we’re doing with the transcribathon, these stories all kind of rise to the surface.”

“It’s an important form of public engagement,” added digital humanities librarian Francesca Giannetti, who also helped organize the event. “Obviously there’s value in having these documents transcribed, so the end product is desirable – but I think even the process of doing the transcription helps people to learn about this history, to learn about why transcription is important and why we still do it.”

The fight for women's suffrage is often considered the largest reform movement in United States history, tracing its roots to the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848—organized, among others, by Stanton herself—through 1920, when the 19th Amendment was finally ratified. As the only state to allow women to vote from the country’s founding in 1776, New Jersey occupies a unique space in the suffrage story, though this right was later restricted and would have to be fought for again through much of the 19th century.“These women showed such courage and leadership in just getting the conversation started,” said Ann D. Gordon, research professor emerita and editor of six volumes of Stanton's and Anthony’s papers. “It was complicated because they didn’t have the tools—they couldn’t use Twitter, they didn’t have Facebook groups. So they traveled across the country to make sure everybody started to talk about this subject.”

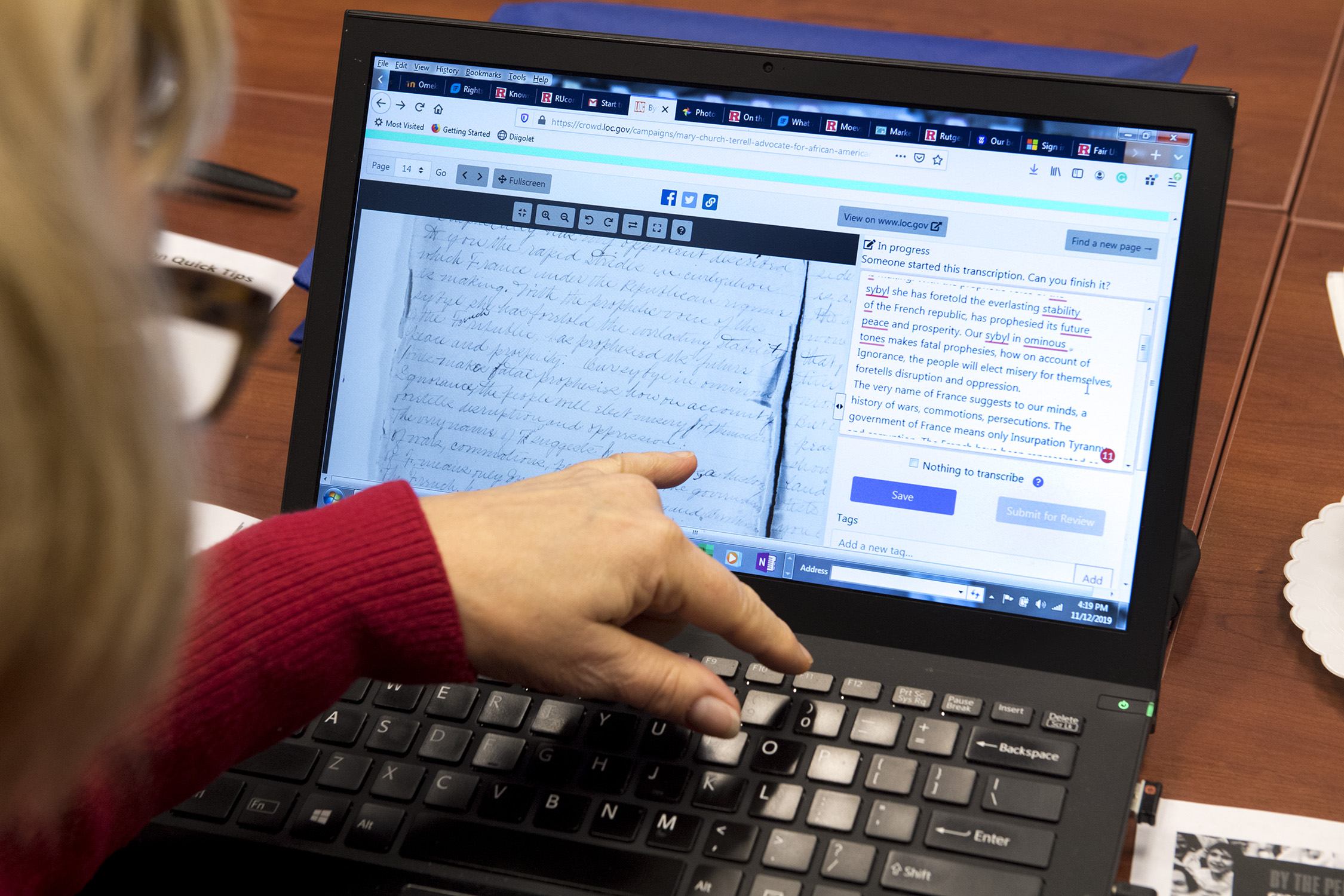

Attendees used By the People—a digital platform developed by the Library of Congress to crowdsource transcriptions of historical documents in its collections—to explore troves of correspondence, diaries, speeches, legal documents, and other matter written by the suffragists. They transcribed and tagged these documents to facilitate keyword searching by researchers. In the process, participants developed a more intimate portrait of the women who advocated bravely for change in a culture that viewed them as little more than wives, mothers, and homemakers.

Noel Dempsey, a history major in the School of Arts and Sciences, reviewed transcriptions from the diary of Terrell, a prominent voice of African-American suffrage. “I feel like I got a more personal insight,” she said. “It was really interesting because there’s still the same barriers. They take different forms today, but you see a lot of the same issues still happening.”For Christopher Chan, a School of Arts and Sciences student double majoring in history and anthropology, the event was a chance to learn lessons from the past. “It gives us a glimpse of how people lived back then and how similar things are to contemporary times,” he said. “It’s important to research these things because it gives us an understanding of the core social issues we still deal with today, so that we can make better policies to address these problems.”

Gordon noted that the participatory element of events like the Transcribathon help underscore history’s relevance. “It’s a way for us to demonstrate that history is something that everyone is affected by and everyone can participate in,” she said.

“What we’re trying to do is create opportunities to think about what history means on a day-to-day basis in our lives,” added O’Brassill-Kulfan. “How do we learn about history? Where do we learn it? Who constructs those narratives? What gaps are there?”

“It’s about putting history into action,” she said.