Rutgers Professor of Microbiology Selman Waksman won the 1952 Nobel Prize in

Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of streptomycin. Working at Rutgers’ College of Agriculture, Waksman and his students

spent nearly three decades analyzing soil microbes before they isolated and

identified the antibiotic streptomycin in 1943, which helped combat the scourge

of tuberculosis during the 20th century.

Waksman and most of his co-workers are long gone, but his legacy lives on.

With the emergence of drug resistant bacteria that cause diseases, such as

tuberculosis, the search for new antibiotics has become a priority. At Rutgers’

Biotechnology Center for Agriculture and the

Environment, molecular biologist Gerben Zylstra leads an initiative that picks

up where Waksman left off, but now employing molecular tools

to streamline and accelerate laboratory processes.

The first challenge the new generation of researchers face, however, is that

the discovery potential of our local soils was exhausted by Waksman’s group. Continued

soil testing would only show bacteria they had already found, over and over.

Thus, the search for the small number of as yet undiscovered microbes and

antibiotics has become a much more challenging and labor intensive process.

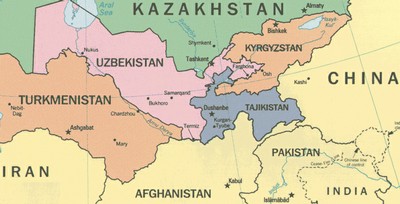

But shifting the search to the other side of the world has now expanded the

horizons for discovery. Through Professor Ilya Raskin’s Global Institute for

BioExploration, Zylstra is working with microbial biochemist Jerry Kukor and

marine microbiologist Lee Kerkhof in the central Asian republic of Kyrgyzstan. The

unexplored soils in this exotic locale contain unique bacteria that the

researchers hope will yield new and different chemicals with antibiotic

properties.

These 21st century researchers are still faced with the arduous

task of screening the

thousands of new Asian soils and microbes in the hope of

finding new antibiotic chemicals.

The Rutgers team is now employing

sophisticated molecular tools, first in pre-screening the soils for the DNA of

new microbes or of new ways to produce chemicals. If the sample tests positive,

they isolate the bacteria that match the test results, and grow them to produce

the chemicals which are then analyzed for antibiotic potential.

However, some bacteria cannot grow in the laboratory – only in their home

soils – so a different approach is used, called metagenomics. This is the pursuit of genetic information in the

absence of lab cultures of microbes, a field in which School of Environmental

and Biological Sciences Dean Robert M. Goodman did some pioneering work.

In this cutting-edge technique, researchers isolate all of the DNA from a soil

sample and clone it. The particular bacterium need not be identified. The focus

is solely on finding genes that make chemicals that may have antibiotic

properties.

“You can go directly after those genes and fish them out, put them in a

bacterium that you can work with in the lab and, hopefully, it will start to

make something that’s new and different,” Zylstra explained.