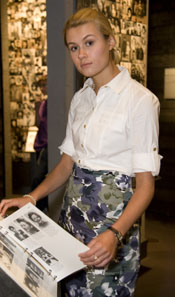

Credit: Courtesy of the Museum of Jewish Heritage

Members of Samuel Weiner’s family fled Germany in the 1930s,

immigrating to what was then Palestine just ahead of the Nazi rampage through

Europe. A close family friend survived the death camps, and the Rutgers senior

says he has been conscious of the unspeakable destruction the Holocaust wrought

since he was 5 or 6.

Corinne Burzichelli, a junior at Rutgers and daughter of a

Roman Catholic family, knew no one who was touched personally by Adolf Hitler

and his followers. It wasn’t until fourth grade, when the Bridgewater resident

picked up a copy of Number the Stars,

a young adult novel, that she learned of the murders of 6 million Jews and 5

million others at the hands of the Nazis.

Now Buzichelli and Weiner are immersed in Holocaust

education, with the goal of passing that knowledge on to the next generation.

As interns with Museum of Jewish Heritage – a Living Memorial

to the Holocaust, they have been hearing testimony from Holocaust survivors,

examining the museum’s exhibitions and artifacts, and attending seminars led by

international scholars.

Armed with new insights, they visited middle schools and

high schools throughout the state earlier this semester to give presentations,

and later shepherded their young charges through the museum for a compelling – often

intense – tour called “Meeting Hate with Humanity.”

“It was the first time at a Holocaust museum for many of

them, and there are sections of the museum where you can’t help be a little bit

horrified,” says Weiner, a resident of Paramus who is pursuing a double major

in Jewish studies and political science in Rutgers’ School of Arts and

Sciences.

The Lipper Internship

Program sends college students like Weiner and Burzichelli into schools

throughout the northeast United States with a message of tolerance and

co-existence. Betsy Aldredge, public relations manager for the museum,

estimates that the program has reached more than 48,000 young people in its 14

years of existence.

Samuel Weiner also interned at the museum.

“The interns are closer to the students’ age than the

teachers, and the younger people feel more comfortable asking them questions,”

Aldredge says.

The internships are open to undergraduates and graduate

students. Most tend to be majoring in history, communications, political

science, or Jewish studies, but any student at a college within a four-hour

driving distance to New York City is eligible.

Participants can choose to receive a stipend or apply the

experience toward academic credits. And while many of the interns are Jewish, the program includes a wide range of religions and ethnicities.

Hannah Johnson, a Rutgers junior from Branchburg with a

double major in history and Jewish studies, identifies herself as an

evangelical Christian. She served as a Lipper intern in the spring of 2011,

interacting with students in Manalapan, Keenesburg, and Passaic.

“The fact that the interns were such a mixed group added a lot of

dimension, because it allowed us to talk to fellow students our age who had a

direct connection to the Holocaust and with other people like me, who have no

connection but who know this is something that should never happen again.

“It’s not just a Jewish issue, it’s a human issue,” says

Johnson, adding that hearing firsthand stories from survivors as part of the

internship allowed her to personalize the impact of state-sponsored mass

genocide in the classrooms she visited.

“My students had definitely learned about the numbers before

we came, but we taught them about the personal stories. They heard the more

human side of things. In the middle schools, in particular, they had a lot of

questions – they wanted to know why, they wanted details. They were really,

really interested,” Johnson says.

For 2005 Rutgers graduate Amy Weiss, now studying for a Ph.D.

in history and Judaic studies at New York University, the internship was a revelation.

“Growing up, I personally had no immediate family connection

with the Holocaust. Going to Rutgers, getting a degree in Jewish studies, led

me to want to know more about it,” says Weiss, originally from New Providence.

“I’m driven by the philosophy of ‘Never again.’ The museum focuses on how we can

connect the lessons of the Holocaust to daily life – why, 60 to 70 years later,

are genocides still going on?”

She believes working at the Jewish heritage museum made her

a better teacher, preparing her to interact with students and field questions

on her feet. Five years after the internship, Weiss continues to lead groups of

middle and high school students through the facility several times a month.

For Burzichelli, the experience boils down to an adjustment

in her perception of the past and its relevance to the present.

“I used to think the Holocaust was about remembering those

who died,” she says. “Now I know it’s about keeping their memory alive.”